towards fully-automated citation screening

abstract

Citation screening is one of the most resource intensive stages of conducting a systematic review, making it ripe for automation. And while machine learning tools have been developped over the years to try and assist researchers during the screening stage, these have predominantly been semi-automated solutions relying on part of the screening process to still be performed manually by experts. The most promising attempts at fully-automating the process have been in the form of classifier models, with most recent approaches trying to incorporate large language models (LLMs) into the process. However, research as of yet has been largely exploratory, producing complex systems that rely on abnormal candidate citation features and varying degrees of expert input, that are optimised with manual prompts and benchmarked on small, ad-hoc datasets. This paper leverages advancements in language model (LM) prompting and AI engineering to create the the first fully-automated LLM-driven pipeline for biomedical citation screening. Designed with simplicity and minimisation of expert input in mind, the pipeline was automatically optimised and benchmarked on the CLEF2019 dataset, producing state-of-the-art results in key classification metrics such as: recall, F1, F3, and WSS, outperforming previous works in the field.

preface

I couldn’t have guessed at the start of my degree that I would end it exploring ways to automate evidence synthesis methods using machine learning (ML) techniques. While I had heard about machine learning before enrolling at UCL, I knew nothing of systematic reviews (SRs) let alone the broader field of evidence synthesis.

By happenstance, halfway through my degree, I ended up working part-time at a small company developping natural language processing (NLP) pipelines that used Large Language Models (LLMs) to perform complex sentiment analysis. I didn’t know it at the time, but doing so was a major stepping stone to working with Professor James Thomas as a research assistant. During which, I learnt more about evidence synthesis and the growing challenge of synthesising knowledge across ever growing bodies of research.

Both the rate and amount of research being conducted across all disciplines is staggering and only growing. The logistics of keeping track of, let alone surveying and syntehsising the evolution of knowledge within fields, borders on the impossible. A fact of growing concern in a world increasingly dependent on research-backed or researched-informed decisions, especially at the political/policy level.

One way to address this issue is with technology: can we develop systems or tools that make tractable the production, management, and synthesis of the large knowledge enterprises we have today?

In my case, and in the case of this dissertation, I wanted to make some small progress on a tiny part of that problem. In particular, the problem of speeding up the synthesising of knowledge with systematic reviews through automation.

My time working with LLMs convinced me of their potential to fully-automate the citation screening stage of conducting systematic reviews – an incredibly resource intensive process that requires experts to manually comb through often thousands of studies/citations to find the ones relevant to a review. With that in mind, I turned to the leading research in language model prompting and AI engineering to try and design the highest performing initial citation classifier for initial citation screening I could.

introduction

Systematic reviews (SRs) are one of the most important tools for synthesising evidence across many discplines, particularly in biomedical fields like medecine and pharmacology. Conducting one is a resource intensive, multi-stage, manual process that requires expertise. They typically begin with a search phase that gathers a large set of “candidate documents” across relevant publication databases. Each document is then manually screened for inclusion usually with a first-pass considering only titles and abstracts, before a final, “full-text” pass that considers the entirety of a document.

As the most labour-intensive and time-consuming stage in a SR (Bastian, Glasziou, and Chalmers 2010; Shemilt et al. 2016), citation screening is ripe for automation. And while semi-automated, human-in-the-loop tools have been developped to speed-up the process (Ofori-Boateng et al. 2024; Marshall and Wallace 2019), we have yet to arrive at the holy grail of expert-independent, fully-automated citation screening.

To this end, this paper offers the first, fully-automated language model (LM) pipeline built with DSPy (Khattab et al. 2024), that’s optimised for title/abstract citation screening of biomedical systematic reviews. Given only the title of a propsective SR as input, it predicts whether candidate citations should be included in the review using only their title and abstract.

Benchmarked on 96 reviews from the CLEF dataset (Kanoulas et al. 2019), alongside the 3 SRs used in (Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025), the pipeline, trained and running on GPT4.1-nano (Kumar et al. 2025), produces state-of-the-art (SOTA) results across key classification metrics including: Precision, Recall, F1, F3, B-AC, Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC), and Work Saved by Sampling (WSS) (Cohen et al. 2006), beating out previous works (Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025; Wang et al. 2024).

background & related works

automating systematic reviews

Ever since their inception in the 1970s (Thomas 2024), systematic reviews have been notoriously time consuming and resource intensive to conduct (Borah et al. 2017; Allen and Olkin 1999). So, it’s no surprise that efforts have been made to automate their various stages as early as the turn of the century (Nadkarni 2002; Moher, Schulz, and Altman 2001).

As machine learning and natural language processing (NLP) techniques evolved, they saw increased adoption in the search, screening, and data extraction stages of conducting reviews. Screening saw attempts at incorporating techniques ranging from citation prioritisation (Cohen, Ambert, and McDonagh 2009) and classification (Cohen et al. 2006) to active learning (AL) (Wallace et al. 2010) and reinforcement learning (RL) (Ros, Bjarnason, and Runeson 2017).

However, all these approaches suffer from often times overlapping limitations that heavily restrict their application:

-

Prioritisation techniques:

These only rearrange the order in which candidate citations should be reviewed by researchers by way of confidence scores for inclusion. As a result, they still require expert reviewers to comb through studies and identify a threshold within the reordered documents, rendering these methods only semi-automated, human-in-the-loop ones (Ofori-Boateng et al. 2024).

-

Classification techniques:

The majority of usable classification approaches involve AL, usually requiring human reviewers to screen a subset of candidate citation features (e.g. title, abstracts, etc…) for a single, specific review to train a specialised classifier for it. This makes these semi-automatic, human in-the-loop approaches (Marshall and Wallace 2019) that don’t generalise to all SRs. And while promising attempts at fully automated, general classification have been made, results are still mostly underwhelming and approaches have largely involved complicated ML techniques and feature extraction methods relying on metadata that would otherwise not be considered in traditional, manual screening (i.e. bibliometric features, research question, year, etc…) (Ofori-Boateng et al. 2024).

-

Active learning:

As its name suggests, active learning requires humans in the loop for the system to learn from. They also suffer from the problem of establishing a clear threshold for human invertension (Ofori-Boateng et al. 2024), i.e. when the model has sufficiently learned from the manual labels to be relied on. .

-

Reinforcement learning:

This approach has yet to be really explored. A recent review on SR automation (Marshall and Wallace 2019) seems to have only found one such work (Ros, Bjarnason, and Runeson 2017). The approach happens to also be semi-automated.

In all, attempts at automating systematic review screening with ML have primarily targeted semi-automated solutions, maintaining the need for an expert reviewer in the process. Only classification offers an avenue towards fully-automated screening and removing the need for expert input all together. This is arguably the most ambitious goal to work towards as achieving it would provide impressive time savings in conducting systematic reviews, paving the way to living systematic reviews (Górska and Tacconelli 2024; Simmonds et al. 2022; Thomas et al. 2017).

However, as mentioned, existing fully-automated classification methods have been relatively complex and have lacked the performance and reliability to be used in practice. They have also heavily focused on the biomedical domain, different formalisations of the screening task1, and have validated their results on small datasets (i.e. a dozen or fewer SRs), typically on Cohen et al’s original work (De Bruin et al. 2023; Cohen et al. 2006). All of which undermines their case for immediate widespread adoption. Nevertheless, early results show enough promise to remain hopeful in the potential for generalised, fully-automated citation classifiers.

Large Language Models (LLMs) as screening classifiers

While still nascent, the application of LLMs to screening classification has drawn recent attention with anticipated promise (Lieberum et al. 2025). For the moment, the majority of research remains exploratory and not ready for direct application in research practice, with many works still yet to pass peer-review (Lieberum et al. 2025).

So far, LLMs have been repurposed as zero-shot or few-shot screening classifiers to automate title/abstract and full-text selection in systematic reviews. A majority of validation studies (Gargari et al. 2024; Kataoka et al. 2023; Moreno-Garcia et al. 2023; Galli et al. 2025; Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025; Dennstädt et al. 2024; Oami, Okada, and Nakada 2024; Issaiy et al. 2024) evaluate ChatGPT-3.5 or GPT-4 against small, often ad-hoc SR datasets – often drawn from just one to five published reviews – and measured concordance with human judgments. This narrow scope raises serious doubts around the generalizability of the approaches. There’s also concerns about overfitting: with relatively few validation examples, there’s a chance models may have inadvertently “memorized” examples that overlap with their large-pretraining corpora.

Moreover, the majority of approaches depend heavily on manually crafted prompts encoding expert knowledge like inclusion/exclusion criteria, PICO elements, or research objectives. For instance, (Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025; Gargari et al. 2024; Galli et al. 2025) all refined separate prompts to capture nuanced eligibility rules making use of pre-written inclusion/exclusion criteria or PICO models, while (Khraisha et al. 2024) used a complex prompt engineering strategy to manually tune prompt templates at each stage – from title screening through to full-text review – in an attempt to maintain precision. Such manual prompt engineering is fundamentally brittle (Khattab et al. 2024) which, in this case, strongly inhibits reproducibility; even slight wording changes or temperature settings can markedly alter classification outcomes, as noted by (Kataoka et al. 2023).

What’s more, by including features like inclusion/exclusion criteria, PICO models, or research objectives into the classification task, the application of the resultant classifiers and the degree to which they automate the process are restricted. If any of these approaches were to be used in practice in the writing of a new systematic review, for example. Then researchers would be required to devise inclusion/exclusion criteria, PICO models, research objectives, etc… These details should be extraneous to an ideal, fully-automated citation screener capable of selecting relevant articles independently of expert researchers.

This work, on the other hand, trains and evaluates a LM pipeline on a combined total of over 120 reviews, an order of magnitude greater than the majority of previous works. It does so with a modular, multi-stage pipeline that is LM-agnostic and automatically optimised removing any manual prompt tuning, guaranteeting reproducibility. What’s more, it achieves SOTA performance over previous works in the least restrictive and expert-dependent way, accurately performing title/abstract classification based on nothing more than SR titles.

methodology

task

This work looked to create the most accurate LM pipeline for first-pass,

title/abstract citation screening under the constraint of requiring the least

amount of expert input as possible. To that end, given a systematic review’s

title, the LM classifier was tasked to return a boolean value, True for

inclusion and False for exclusion, given only a candidate citation’s title and

abstract as input.

datasets

In line with (Opsahl-Ong et al. 2024) recommendations, the design of a citation classifier pipeline in DSPy began with the creation of development, training, and testing/validation datasets.

An initial, exploratory pipeline design phase was conducted using a development set that was drawn from part of the SYNERGY dataset (De Bruin et al. 2023): a collection of 26, majority biomedical, reviews. However, containing only the inclusion results after full-text screening, SYNERGY was quickly dropped in favour of the CLEF2019 dataset (Kanoulas et al. 2019) when it came to training and testing, since it contained the results of both title/abstract and full-text screening.

Building on CLEF2017 and CLEF2018, CLEF2019 introduces additional systematic reviews growing the dataset to a combined total of 128 biomedical reviews of different types. All together, CLEF2019 is approximately split 80-40 between Diagnostic Test Accuracy (DTA) topics and intervention review (Int) topics. It was eventually randomly split 20/80 into a training and test set, in line with (Khattab et al. 2024)’s recommendations. This way, validation on the test set could produce results that could be directly compared to (Wang et al. 2024)’s results.

Finally, a copy of (Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025)’s dataset of 3 SRs was made as an additional test set. It’s smaller size enabled faster, cheaper design iterations than full passes through the CLEF2019 test set would have allowed, while also offering another opportunity to compare the performance of this work’s solution against previous results.

data preprocessing

Each dataset (i.e. SYNERGY, CLEF, and (Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025)’s) was initially structured and formatted differently. As a result, each was first parsed and formatted into a unified dataset template that stored for each candidate citation: an ID, the ID of the SR it was a candidate for, its title, its abstract, whether it passed title/abstract screening (i.e. “screening 1”), and whether passed full-text screening (i.e. “screening 2”).2 In the process, datasets were also cleaned and emptied of empty/NaN values, with rows that didn’t include both titles and abstracts being removed entirely.

From there, a training set was created by randomly sampling 24 SRs from the newly processed CLEF2019 data, with the remaining 96 SRs, totalling 348251 candidate citations, forming the test set (Table 2). However, to allow for rapid iteration on training parameters and pipeline designs, the size of the training set was restricted such that each of the 24 sampled SRs only contributed either 30 or 31 citations to the training set. This was done by randomly undersampling citations in each of the 24 training SRs in such a way that the proportion of positively labelled citations (i.e. passed title/abstract screening) in the final 30/31 selected citations, was randomly selected between 0% and 50%. In doing so, the imabalanced nature of the data and the variance in imbalance could be preserved, while also guaranteeing a certain proportion of positive labels. In the end, the training set culminated in a collection of 732 citations with 280 positive some \(\approx\) 38.25% (Table 1).

Finally, reproducing (Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025)’s approach, 3 their SRs were preprocessed into a combined test set (Table 3), after first coding the from “Review I” to “Review III” to avoid repeating their long titles:

- “Review I” for the “Economic Evaluations of Musculo-Skeletal Physiotherapy (Physio)” review (Baumbach et al. 2022).

- “Review II” for “Treatment in Hereditary Peripheral Neuropathies (Neuro)” review (Jennings et al. 2021).

- “Review III” for “Cost-Effectiveness of AI in Healthcare (DigiHealth)” review (Wolff et al. 2020).

| Counts | CLEF2017 | CLEF2018 | CLEF2019 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of SRs | 6 | 7 | 11 |

| Total number of citations | 181 | 214 | 337 |

| Passed Screening 1 | 74 | 91 | 115 |

| Passed Screening 2 | 23 | 27 | 68 |

| Counts | CLEF2017 | CLEF2018 | CLEF2019 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of SRs | 32 | 22 | 42 |

| Total number of citations | 159590 | 107758 | 80903 |

| Passed Screening 1 | 2647 | 3205 | 1734 |

| Passed Screening 2 | 646 | 548 | 959 |

| Review I (Physio) | Review II (Neuro) | Review III (DigiHealth) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of citations | 4501 | 1650 | 66 |

| Passed Screening 1 | 172 | 113 | 45 |

| Passed Screening 2 | 70 | 22 | 6 |

pipeline design

Simple pipeline designs were considered at first. Ones in which the LM would be

asked to directly predict inclusion from just a SR’s title alongside the title

and abstract of a candidate citation. This straightforward transformation was

captured in the following dspy.Signature:

class Relevance(dspy.Signature):

"""Classify a citation's relevance to a systematic review."""

sr_title: str = dspy.InputField()

citation_title: str = dspy.InputField()

citation_abstract: str = dspy.InputField()

relevant: bool = dspy.OutputField()

confidence: float = dspy.OutputField()

Early development results showed that pairing this signature with Chain of Thought (CoT) prompting (Wei et al. 2022) clearly outperformed direct prediction. But performance was still lackluster, calling for more sophisticated designs that leveraged CoT.

Later iterations tried to incorporate insights from (Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025), namely the importance of inclusion/exclusion criteria. This inspired a two-stage pipeline that first generated a list of inclusion/exclusion criteria for a given SR title, before evaluating a candidate title/abstract pair against those criteria, producing a list of boolean values representing which criteria were satisfied. Inclusion could then be decided based on the number of criteria that held for a candidate citation.

class ClassifyByInclusionExclusion(dspy.Module):

def __init__(self):

self.generate_criteria = dspy.ChainOfThought(InclusionExclusionCriteria)

self.evaluate_criteria = dspy.ChainOfThought(CheckCriteria)

def forward(self, sr_title: str, citation_title: str, citation_abstract: str):

criteria = self.generate_criteria(

systematic_review_title=sr_title

).criteria

return self.evaluate_criteria(criteria=criteria,

citation_title=citation_title,

citation_abstract=citation_abstract)

class InclusionExclusionCriteria(dspy.Signature):

"""

Output a set of inclusion/exclusion criteria for the screening process of a systematic review.

"""

sr_title: str = dspy.InputField(desc="Title of the systematic review.")

criteria: list[str] = dspy.OutputField(

desc="Inclusion/exclusion criteria and their descrptions."

)

class CheckCriteria(dspy.Signature):

"""

Verify which criteria are satisfied by the title and abstract of a candidate citation.

"""

criteria: list[str] = dspy.InputField()

citation_title: str = dspy.InputField()

citation_abstract: str = dspy.InputField()

satisfied: list[bool] = dspy.OutputField(

desc="Whether each criteria is satisfied or not."

)

Different conditions were tested to decide when a list of verified

inclusion/exclusion criteria qualified the underlying candidate citation as

relevant to a review, including: requiring a majority of the criteria to be true

and requiring all of them to be true. However, in line with

(Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025)’s findings, these conditions for inclusion were

too stringent and didn’t generalise well. So, taking inspiration again from

their work training a Random Forest model on their LLM-generated criteria, a

final pipeline was designed that extended ClassifyByInclusionExclusion. In

particular, it introduced a stage to generate a decision tree for a given set of

inclusion/exclusion criteria, as well as a stage to traverse a decision tree

given a list of evaluated criteria:

class ClassifyByTreeInclusionExclusion(dspy.Module):

def __init__(self):

self.generate_criteria = dspy.ChainOfThought(InclusionExclusionCriteria)

self.generate_tree = dspy.ChainOfThought(DecisionTree)

self.evaluate_criteria = dspy.ChainOfThought(CheckCriteria)

self.evaluate_tree = dspy.ChainOfThought(RelevanceFromTree)

def forward(self, sr_title: str, citation_title: str, citation_abstract: str):

criteria_pred = self.generate_criteria(

sr_title=sr_title

)

tree_pred = self.generate_tree(

sr_title=sr_title,

criteria=criteria_pred.criteria

)

satisfied_pred = self.evaluate_criteria(

criteria=criteria_pred.criteria,

citation_title=citation_title,

citation_abstract=citation_abstract

)

relevance_pred = self.evaluate_tree(tree=tree_pred.tree,

satisfied=satisfied_pred.satisfied)

# add the previous predictions for posterity

relevance_pred.criteria_pred = criteria_pred

relevance_pred.tree_pred = tree_pred

relevance_pred.satisfied_pred = satisfied_pred

return relevance_pred

class DecisionTree(dspy.Signature):

"""

Output a decision tree for a set of inclusion/exclusion criteria

to be used in a citation screening process for a systematic review.

"""

sr_title: str = dspy.InputField(

desc="The title of the systematic review that citations are being screened for."

)

criteria: list[str] = dspy.InputField(

desc="The inclusion/exclusion criteria used for screening."

)

tree: str = dspy.OutputField(

desc="A decision tree that dictates whether a citation should be included in a systematic review by the inclusion/exclusion criteria the citation satisfies."

)

class RelevanceFromTree(dspy.Signature):

"""

Decide whether a citation should be included in a systematic review by traversing

the decision tree of the review's screening process with the list of the inclusion/criteria

that were satisfied or not by the citation under consideration.

"""

tree: str = dspy.InputField(desc="The decision tree to traverse.")

satisfied: list[bool] = dspy.InputField(

desc="A list of which criteria were satisfied and which weren't."

)

included: bool = dspy.OutputField(

desc="Whether the citation should therefore be included or not."

)

training & evaluation

Considered LMs

While local instances of Gemma 3 4b and 1b (Farabet and Warkentin 2025) were used during pipeline development, once the pipeline design finalised, it was trained on the CLEF2019 training set using GPT4.1-nano. For the simple reason that GPT-4.1 offered the necessary scale to optimise multiple variants of the final pipeline and evaluate the large testing set in reasonable time.

Optimisers & Training Parameters

Given the training set’s size, in line with recommendations,

BootstrapFewShotWithRandomSearch and MIPROv2 (Opsahl-Ong et al. 2024) were

the primary optimisers used. Development largely began with the former but

quickly moved to the latter to allow for faster iteration, thanks to its quicker

training time. The final pipeline and its optimised variants were all trained

using MIPROv2. Default parameters were used for both optimisers throughout.

Evaluation Measures

-

Training

In line with existing research, a suite of classification metrics were selected, all based around the core classification metrics: True Positives (TP), True Negatives (TN), False Positives (FP), and False Negatives (FN).

During development different metrics were tested to explore their impact on performance. Since the training set included the results of title/abstract screening and full-text screening, some training runs were performed that looked to maximise performance predicting title/abstract labels only, full-text labels only, and a combination of the two.

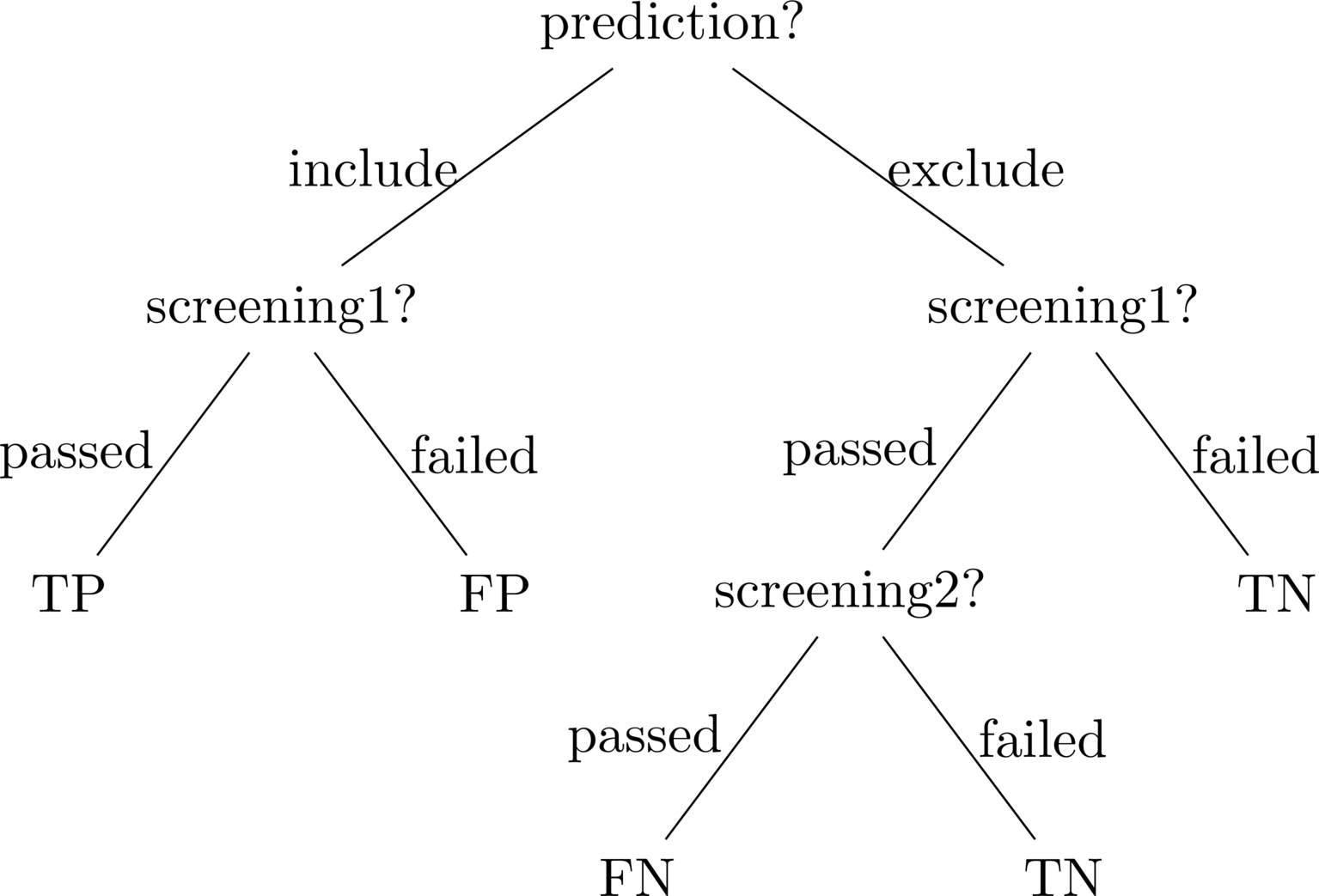

The combination approach was born out of the realisation that in looking to create an accurate first-pass, title/abstract classifier, there was little sense in punishing the system for predicting a citation should be excluded if it happened to actually pass title/abstract screening but fail full-text screening. In this way, the combined approach involved the creation of a metric that considered a prediction to be a FN only if it predicted the exclusion of a citation that had passed full-text screening. Similarly, a prediction was considered a TP if it predicted the inclusion of a citation that had passed title/abstract screening, irrespective of whether it passed full-text screening. The following decision tree illustrates this combined approach, where “screening1” referes to title/abstract screening, and “screening2” refers to full-text screening:

Figure 1: Decision Tree of

straight_validateDSPy metric.The decision tree was then implemented into the following DSPy metric:

def straight_validate(example, pred, trace=None): if pred.included: if example.screening1: return True else: return False else: if example.screening1: if example.screening2: return False else: return True else: return TrueIn the end, only this metric (i.e.

straight_validate) and a variant calledmax_recall, that only punished FNs by returningTruefor everything but FNs, were used to train 2 final, optimised GPT4.1-nano pipelines. With the aim formax_recallto maximise the system’s ability to achieve the standard threshold recall rate of 0.95 in systematic review screening (Crumley et al. 2005; Callaghan and Müller-Hansen 2020).

-

Validation

Building on the same notions of TP, TN, FP, FN implemented in

straight_validate, the traditional classification metrics of accuracy, precision, recall and specificity were used to measure final pipeline performance in the two test sets (i.e. 96 SRs from CLEF2019 and the 3 SRs from (Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025)). Due to the imbalanced nature of citation screening as a classification task, i.e. more citations are excluded then included, balanced accuracy (B-AC), the mean of recall and specificity, was also used. Both F1 and F3 scores were calculated to compare performance to (Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025) and (Wang et al. 2024)’s results respectively. For the same reason, Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) and Work Saved by Sampling (WSS) (Cohen et al. 2006) were also calculated.But note that, as a system designed to maximise performance on initial title/abstract screening, and not agreement with human reviewers, as highlighted by the

straight_validatemetric, Cohen’s kappa (Cohen 1960), and by extension, prevalance-adjusted bias-adjusted kappa (PABAK) were not calculated.

results

The process of evaluating both test sets on the final

ClassifyByTreeInclusinExclusion DSPy module/pipeline using GPT4.1-nano was

identical. In both cases, for each candidate citation in a set, input tuples

containing a systematic review title and candidate citation title and abstract

were fed as examples into an optimised pipeline. All results were recorded

including predictions and LM reasoning steps of intermediary stages. But focus

was mainly placed on the final predicted boolean value: included.

Three variants of the pipeline were created, 2 of which trained:

- Unoptimised

- Optimised with respect to the

straight_validatemetric. - Optimised with respect to the

max_recallmetric.

However, because of time and cost constraints, only the

(Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025) test set was evaluated on all three variants due

to its smaller size. The CLEF2019 test set was only evaluated on the max_recall

optimised version to make results as comparable to (Wang et al. 2024)’s work

as possible.

(Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025) test set

To direclty compare performance against (Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025)’s results, only the relevant classification metrics were calculated: precision, recall, specificity, F1, and MCC.

An overview of metric performance is provided in (Table 4).

| Review | Optimisation Type | Precision | Recall | Specificity | F1 | MCC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Review I | max_recall |

0.10 | 0.96 | 0.67 | 0.18 | 0.25 |

straight_validate |

0.21 | 0.68 | 0.93 | 0.32 | 0.35 | |

| unoptimised | 0.11 | 0.99 | 0.70 | 0.20 | 0.28 | |

| Review II | max_recall |

0.15 | 0.93 | 0.76 | 0.25 | 0.31 |

straight_validate |

0.30 | 0.86 | 0.93 | 0.44 | 0.48 | |

| unoptimised | 0.34 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.50 | 0.55 | |

| Review III | max_recall |

0.77 | 1.00 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.82 |

straight_validate |

0.67 | 0.29 | 0.98 | 0.40 | 0.40 | |

| unoptimised | 0.71 | 0.50 | 0.96 | 0.59 | 0.54 |

To gauge the potential performance uplift of optimisation more broadly, and to

test whether targeted optimisation approaches with respect to specific metrics

like max_recall had any merit, all evaluation metrics were calculated and

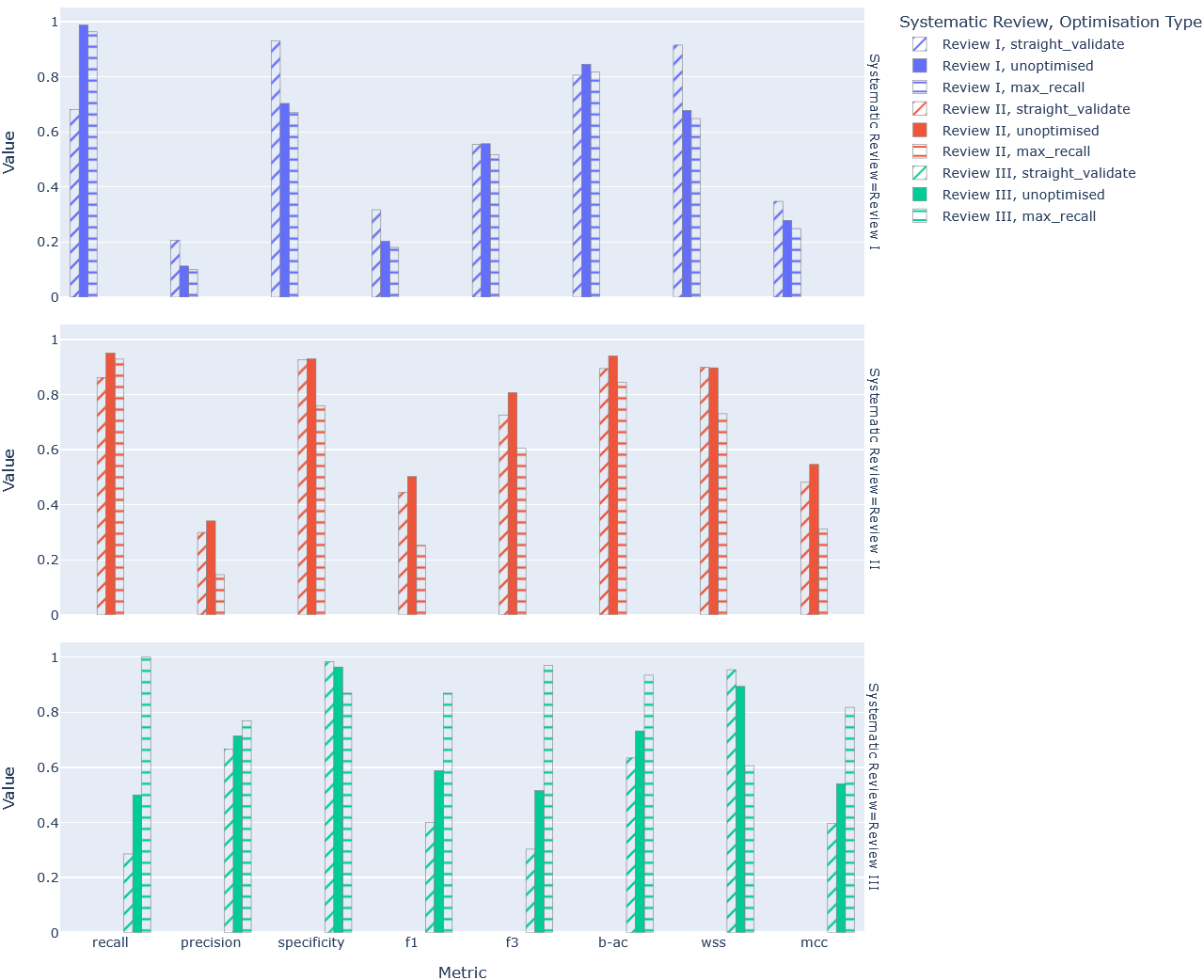

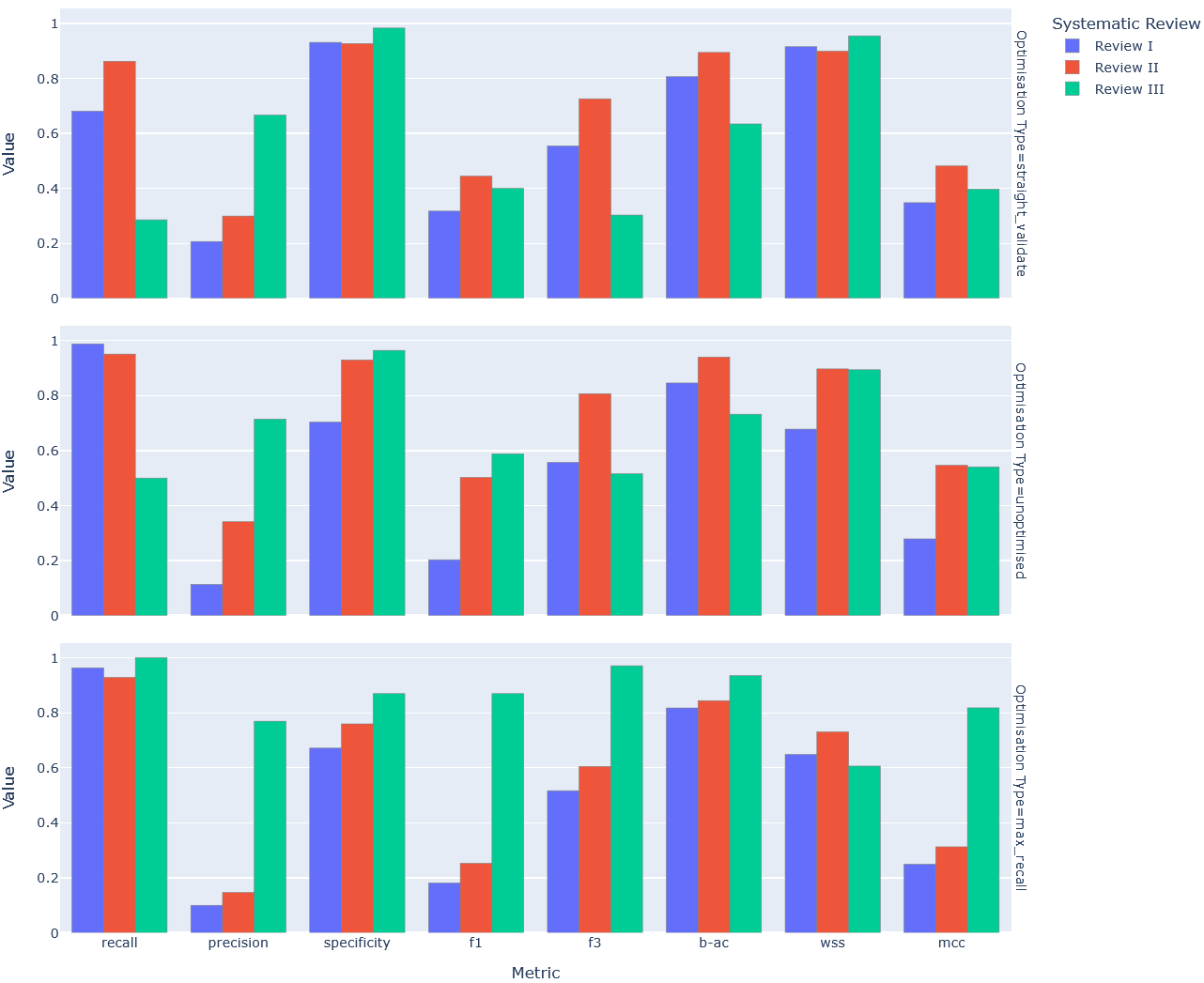

visualised in a bar chart (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Comparative bar chart of key classification metric performance by review.

A similar bar chart was also produced to test whether optimisation (in any form) improved performance consistency by visualising all metrics by optimisation type (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Comparative bar chart of key classification metric performance by optimisation type

CLEF2019 test set

In the same vein as the (Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025) test set, only the

metrics relevant for comparison with (Wang et al. 2024)’s work were

calculated for the CLEF2019 test set, namely: precision, B-AC, F3, WSS3, and

recall. For that same reason (as well as cost reasons), the test set was only

evaluated on the max_recall variant of the final pipeline. This way, results

could compete with (Wang et al. 2024)’s top performing models calibrated for

0.95 or 1 (i.e. perfect) recall.

However, since the CLEF2019 test set contains 96 SRs instead of (Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025)’s 3, the pipeline’s performance on each invidiual review is not reported. Instead, the lower quartile, median, upper quartile, and mean of the metrics were calculated across each CLEF dataset contained within CLEF2019 (i.e. CLEF2017, CLEF2018, CLEF2019), and aggregated into (Table 5), mirroring (Wang et al. 2024)’s presentation.

| Dataset | Metric | Lower Quartile | Median | Upper Quartile | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLEF2017 | Precision | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.20 | 0.14 |

| B-AC | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.94 | 0.89 | |

| F3 | 0.31 | 0.48 | 0.70 | 0.49 | |

| WSS | 0.77 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.81 | |

| Recall | 0.96 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.94 | |

| CLEF2018 | Precision | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.35 | 0.22 |

| B-AC | 0.89 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.92 | |

| F3 | 0.38 | 0.63 | 0.82 | 0.60 | |

| WSS | 0.78 | 0.84 | 0.91 | 0.83 | |

| Recall | 0.95 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.97 | |

| CLEF2019 | Precision | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.14 |

| B-AC | 0.75 | 0.83 | 0.91 | 0.83 | |

| F3 | 0.26 | 0.50 | 0.69 | 0.47 | |

| WSS | 0.56 | 0.73 | 0.85 | 0.68 | |

| Recall | 0.94 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.95 |

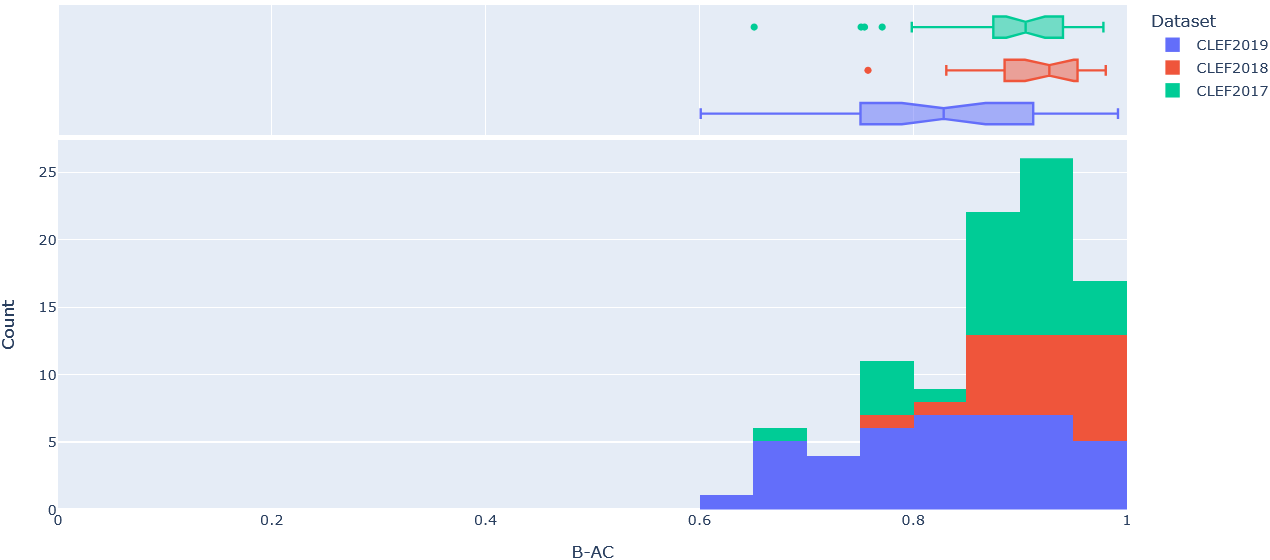

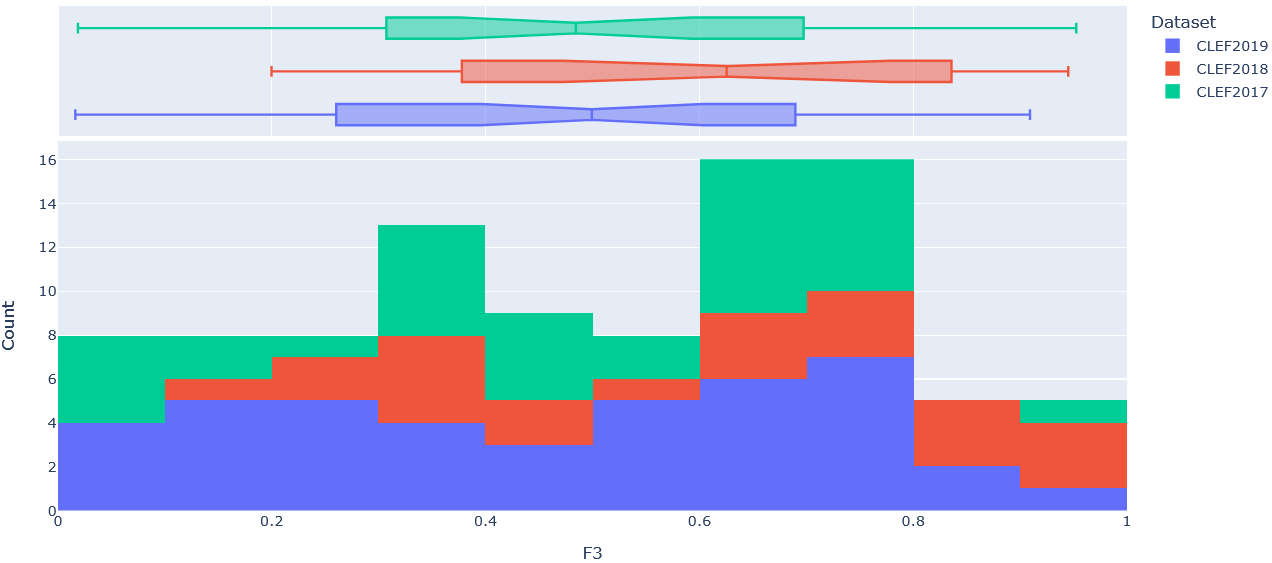

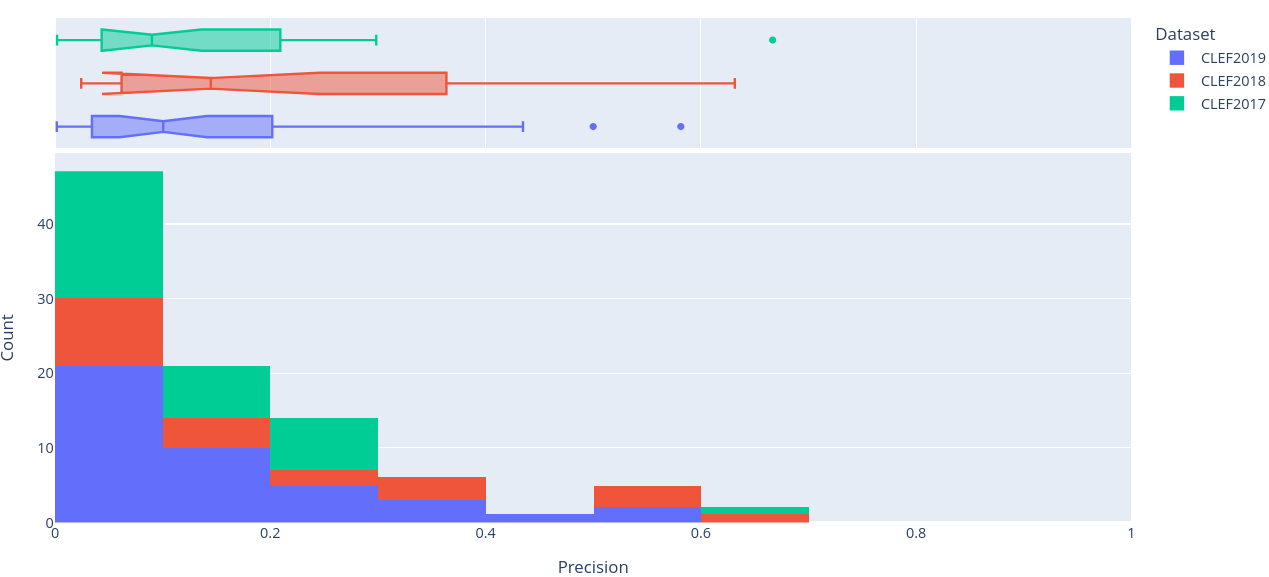

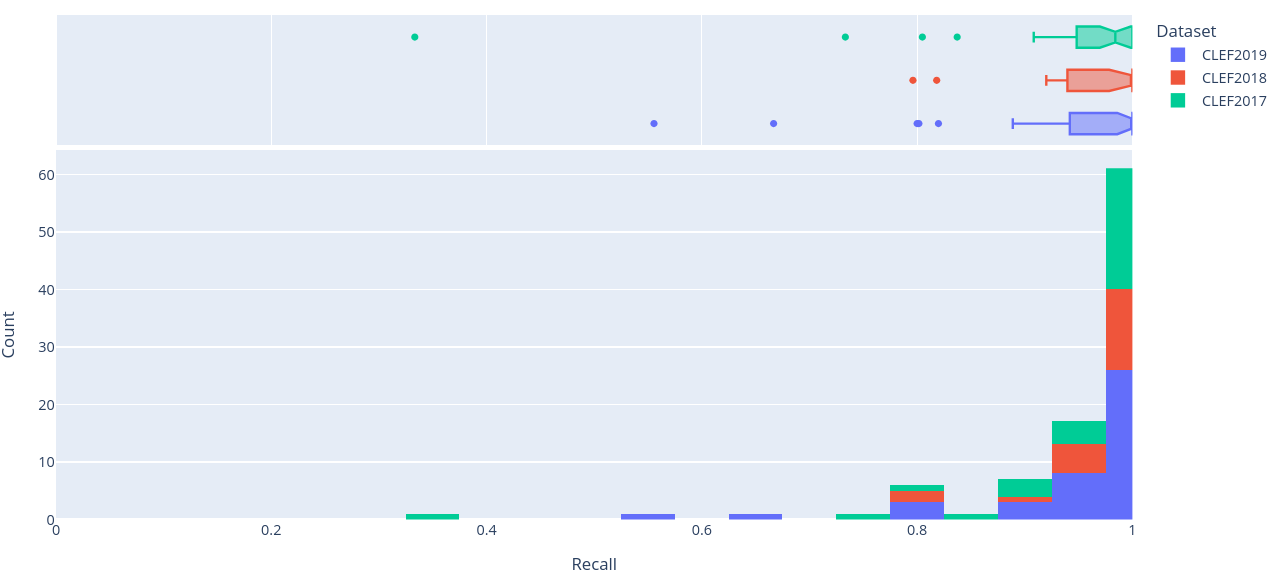

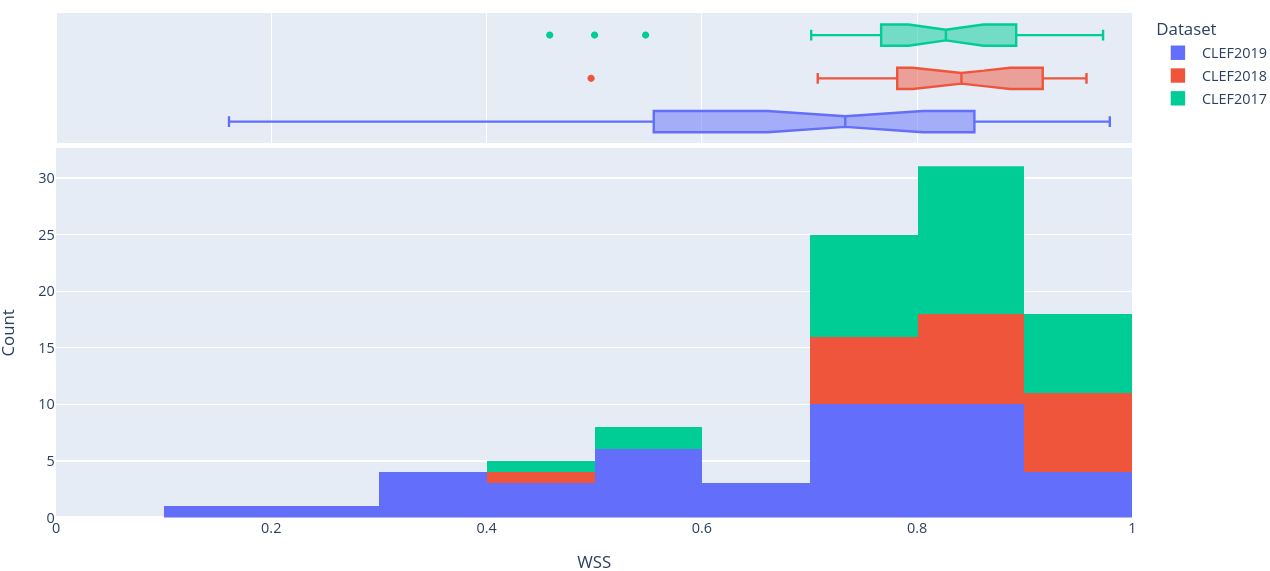

To get a better sense of the underlying distribution of each metric, stacked histograms of each were produced by CLEF dataset year (Figure 4-8).

Figure 4: Stacked histogram of B-AC scores across SRs in CLEF2017, CLEF2018, and CLEF2019 evaluated on the final (i.e. ClassifyByTreeInclusionExclusion) pipeline optimised on max_recall.

Figure 5: Stacked histogram of F3 scores across SRs in CLEF2017, CLEF2018, and CLEF2019 evaluated on the final (i.e. ClassifyByTreeInclusionExclusion) pipeline optimised on max_recall.

Figure 6: Stacked histogram of precision scores across SRs in CLEF2017, CLEF2018, and CLEF2019 evaluated on the final (i.e. ClassifyByTreeInclusionExclusion) pipeline optimised on max_recall.

Figure 7: Stacked histogram of recall scores across SRs in CLEF2017, CLEF2018, and CLEF2019 evaluated on the final (i.e. ClassifyByTreeInclusionExclusion) pipeline optimised on max_recall.

Figure 8: Stacked histogram of WSS scores across SRs in CLEF2017, CLEF2018, and CLEF2019 evaluated on the final (i.e. ClassifyByTreeInclusionExclusion) pipeline optimised on max_recall.

analysis & discussion

pipeline design

On the surface, the performance of the final pipeline is compelling, optimised or not. But it’s worth pointing out that a key benefit of this design is in efficiency.

One main drawback of using LLMs for citation screening, rather than dedicated, purpose-built ML solutions, are the time and monetary costs. The main AI research labs (i.e. OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, etc) charge for their models on a per token basis. So, the more text passed to, and generated by, a private LLM, the more expensive the cost of its prediction, both in terms of the time spent to reach a prediction and the dollars spent to get to it.

An easy workaround is to use free, open source language models that can run locally, as was done in this work while iterating on pipeline design with Gemma3 4b and 1b. But, ultimately, this simply shifts the cost of running a LLM from the provider to the researcher.

Another factor is the size of the LLM. Traditionally, larger models can offer improved performance over smaller ones (Kumar et al. 2025) but their increased size comes with increased costs. And some models are impractically large to be ran locally.

So, when considering LM-driven pipeline designs for citation screening, cost management primarily reduces to:

- Choosing a sufficiently cheap language model.

- Minimising the number of tokens to be passed to, and generated by, the model across a single predictive pass through all stages.

Since DSPy is model agnostic, in so far as the formal definition/specification of a pipeline in Python code is completely decoupled from the LM used to drive it, the choice of LM is largely left to the user/researcher deploying a pipeline in practice. That isn’t to say that LM choice doesn’t affect downstream performance. On the contrary, in this work, early iterations on pipeline design showed a clear drop in performance when evaluating the same pipeline on the smaller Gemma3 1b model, compared to the larger Gemma3 4b one. This could possibly be explained by the fact that smaller models have fewer parameters to “remember” as much domain specific knowledge relevant to the citation screening task from their pretraining corpora. Or, more simply, the widely accepted decrease in LM performance with size could just act as a limiting factor. An idea that might have more merit, seeing as it was observed in pipeline development that Gemma3 1b would more often fail to produce the necessary structured output of intermediary stages of a pipeline compared to Gemma3 4b.

With that said, while (Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025)’s results suggest that smaller LLMs can outperform larger ones, the impact of LLM size on citation screening performance is not clear cut. Least of all in the context of this particular pipeline, let alone in the broader context of screening pipelines implemented and optimised with DSPy.

The only consideration left to control for is the number of tokens required to complete a pass through a given pipeline. Obviously, this will depend entirely on the task at hand, and the tokeniser of the underlying LM. But it will mostly depend on the number of stages in the pipeline and the prompting technique used at each stage. In other words, the amount of work wanting to be done in a stage, and how that work is to be done.

In the case of this work’s final ClassifyByTreeInclusionExclusion pipeline, the

number of stages was a primary concern due to the direct impact it had on

iteration speed. And given Chain of Thought (CoT) prompting was identified early

on as a clear improvement over direct prediction, it was almost immediately

decided to be the default prompting technique for any stage going forward.4 As a

result, beyond reducing the number of stages, the only way of improving pipeline

efficiency was to lean on DSPy’s cacheing.

The final pipeline design does so by effectively repeatedly calling a LM on only

two of ClassifyByTreeInclusionExclusion’s four stages. For a given SR title, the

generate_criteria and generate_tree stage will only be called once in practice

– their cached responses will be used for all future passes through the pipeline

for that SR title. Similarly, seeing as the evaluate_criteria stage produces a

list of boolean values, representing the satisfiability of each

inclusion/exclusion criteria, there is only a finite number of combinations of

such a list, i.e. \(2^{n}\) where \(n\) is the number of inclusion/exclusion

criteria. Therefore, in the worst case, the pipeline’s final stage:

evaluate_tree, will only actually be called a maximum of \(2^{n}\) times. Since

the cached response for this stage will be used whenever the same list of

satisfied inclusion/exclusion criteria is seen more than once.

This approach to pipeline design offers meaningful efficiency gains that are noticeable in practice. When classifying the candidate citations of a given systematic review, the first pass through the pipeline is noticeably slow, requiring sometimes upwards of 10s to complete. But once completed, all future passes for that SR require seconds, if not less, to complete. An observable event made clear by token usage (Table 6).

ClassifyByTreeInclusionExclusion pipeline. Both citations are drawn from the CLEF2019 test set.

| Pass | Counts | unoptimised | straight_validate |

max_recall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Pass | Total number of tokens | 2611 | 2768 | 6730 |

| Prompt tokens | 1673 | 1833 | 5844 | |

| Completion tokens | 938 | 935 | 886 | |

| Subsequent Pass | Total number of tokens | 738 | 1652 | 768 |

| Prompt tokens | 580 | 1352 | 590 | |

| Completion tokens | 154 | 300 | 178 |

interpretation of results

From (Table 4) and (Figure 2) alone it’s not particularly clear whether

optimisation (i.e. straight_validate), let alone targeted optimisation with

max_recall, has produced meaningful performance uplift. In the case of (Table

4), the highest performing version of the pipeline across the 5 metrics is

different for each review:

straight_validateperforms best for Review I.- The unoptimised variant performs best for Review II.

max_recallperforms best for Review III.

A closer look at (Figure 2), and the metrics not included in (Table 4) in particular (i.e. F3, B-AC, WSS), reaffirms this inconsistency. But it isn’t to say that optimisation, targeted or otherwise, hasn’t had any impact. Clearly Review I and Review III show improved performance across the board when evaluated on optimised variants of the pipeline (Table 4). It’s only that optimisation has not been the tide to raise all boats it was expected to be – it doesn’t appear to have smoothed out the variance in performance between reviews (Figure 3).

With that said, the inconsistency in uplift could be explained by a couple of factors:

- The (Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025) test set includes reviews that are very different to those included in the CLEF2019 training set that was used to optimise the pipeline. And it’s possible the optimised pipeline variants may have overfitted to the training set, or simply don’t generalise well for other reasons.

- What’s more, each SR in (Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025) is very different from one another, both at a topic level but also in number of candidate citations, as highlighted by (Table 3). Case in point, Review III only has 66 candidate citations making its metrics sensitive to small changes in the number of TPs, TNs, FPs, and FNs.

Inconsistency notwithstanding, actual performance on the metrics show promise. Looking at (Table 4), the best performing pipeline variant of each review produces high recall rates, all within the standard threshold for review, i.e. 0.95 (Crumley et al. 2005; Callaghan and Müller-Hansen 2020). Similarly, specificity is high across the board suggesting FP rates must be relatively low. And while there is an important degree of variance in F1 scores even between the best performing pipelines across the reviews, it’s clear that with such high recall rates, F1 scores are being dragged down by the noticeably weaker precision rates. This can even be seen on (Figure 2) in the higher F3 scores that attach more importance to recall over precision.

Regardless, these results generally suggest a need for a better tradeoff between precision and recall, whether by independently boosting precision while maintaining high recall rates, or by willing to accept a recall rate below the 0.95 standard. An idea that has some merit considering human reviewers seem to already have \(\approx\) 10% error rate (false inclusion and false exclusion) in title/abstract screening (Wang et al. 2020). A fact that would suggest a classifier capable of achieving a recall rate of 0.95 or higher to have superhuman performance in practice.

Luckily, rebalancing the precision/recall tradeoff seems achievable, espcially

given the effectiveness of targetted optimisation illustrated by max_recall.

Because although this pipeline variant didn’t technically produce the highest

recall rates in Review I and II (Table 4), scores were within 2-3% of the

highest while also being universally higher than the recall rates achieved by

the straight_validate optimised variant. Taken together, it’s clear that

optimising for a specific metric like recall has a meaningful effect, one that

can arguably be seen in the CLEF2019 test set in (Figure 7) and (Table 5),

despite there being no rates of variant pipelines to compare them to.

Comparison with (Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025)

Before comparing results, it’s important to note that while the final pipeline was heavily inspired by (Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025)’s approach, this work’s implementation is both simpler and less reliant on expert input. In particular, (Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025)’s model requires expert written inclusion/exclusion as input and uses a custom trained Random Forest classifier to make the final classification decision, taking a list representing which criteria were satisfied as judged by a LLM as input. In effect, (Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025)’s LLM-driven citation screening model is really only LLM-driven in so far as it uses a LM to evaluate a candidate citation title/abstract pair against a pre-written set of inclusion/exclusion criteria. To that extent, this work’s model is more “end-to-end”, in that both inclusion/exclusion criteria writing, and final classification for inclusion is actually performed by a LLM instead of a human and secondary ML model.

With that in mind, comparing performance metrics from (Table 4), it’s clear that (Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025)’s model prioritises precision over recall. So, while this work’s pipeline offers marginal precision gains on Review I over a select few LLMs benchmarked by (Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025), no version of this pipeline (optimised or not) can compete with their model on precision. On the other hand, the opposite is true of recall – optimised or not5, the final pipeline beats out the higest recall rates attained by any of their LLMs across all 3 reviews. And if citation screening is to be fully automated, it makes sense for recall to be the priority so as to ensure the comprehensiveness of a review. So, from a practical perspective there’s little doubt that this pipeline is of greater immediate utility than (Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025)’s model.

The other metrics affirm this. The best performing pipeline variant of each

review match the high specificity seen across the LLMs benchmarked by

(Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025). Similarly, the majority of F1 and MCC scores

are matched or exceeded by the best performing pipeline variant of each review,

with the the exception of max_recall on Review III beating out any of

(Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025)’s F1 or MCC scores by a wide margin. Having said

that, comparing the best performing pipeline variant of each review isn’t

entirely fair. It ignores the blatent performance inconsistency across the 3

SRs. If performance comparisons had to be restricted to a single variant for all 3

reviews, performance across the board (except for recall) would be largely

matched with or worse than (Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025)’s results for 2 of

the 3 reviews.

So, until performance inconsistencies are addressed, it’s not entirely fair to claim that this pipelne and approach to automating citation screening universally beats out (Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025). However, it is fair to say that they show more promise. Especially in light of the fact that (Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025)’s Random Forest model, that performs the actual classification, is trained on the data (i.e. the 3 SRs being benchmarked). An important, fact that recontextualises this work’s results as out-of-sample performance compared to (Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025)’s in-sample performance.

Comparison with (S. Wang et al. 2024)

Similar this work’s approach, (Wang et al. 2024) does use a LLM to directly predict inclusion. However, they do so by framing the task as a “yes” or “no” question posed to the LLM directly asking whether a candidate document should be included or not. They insert the title of a systematic review along with, what seems to be the entirety of a candidate document, into a prompt template. They then act on the probabilities of the next predicted token being “yes” or “no”. In the case of “yes” having a higher probability, the document is considered to be classified as included, it’s excluded otherwise. They then build on this approach by calibrating it to meet a specific target recall rate, e.g. 0.95, by calculating the difference between the probabilities of the “yes” and “no” tokens being predicted next for every candidate document of a given SR (title), before calculating a threshold for inclusion based on that difference that would guarantee a specified minimum recall rate.

It’s this calibrated approach that produces the best recall rates, and it’s the

reason why, given the time and cost constraints, only the max_recall optimised

variant of the final ClassifyTreeByInclusionExclusion was evaluated on the 96

reviews in the CLEF2019 test set. As a result, it makes sense to compare the

optimised pipeline’s performance only against the best performing of the

calibrated variants of (Wang et al. 2024)’s model. Just note that it’s unclear

whether they performed title/abstract or full-text screening. Their use of

CLEF2019 seems to suggest the former but it doesn’t seem to have been made

explicit. Likewise, it’s unclear whether their performance metrics are median or

mean averages. So, for the sake of being thorough, both will be compared.

Looking first at CLEF2017 reviews, (Wang et al. 2024)’s highest average recall rate is achieved by a LlaMa2-7b-ins model calibrated for perfect recall (i.e. \(r=1\)). It achieves a recall rate of .99 compared to the final pipeline’s median and mean scores of.98 and .94 respectively. So, while (Wang et al. 2024)’s model narrowly beats out the pipeline, it’s not a particularly meaningful victory seeing as both methods produce results within (or just under) the standard threshold of .95. However, this is the only place (Wang et al. 2024) pulls away. The pipeline beats out the calibrated LlaMa2-7b-ins model in all other metrics – in precision, B-AC, F3, and WSS.

In fact, comparing the lowest of the pipeline’s median and mean results, to the highest scores achieved by any of (Wang et al. 2024)’s calibrated models (i.e. LlaMa2-7b-ins, LlaMa2-13b- ins, BioBERT, and an ensemble of the three), whether calibrated for .95 or 1 recall6, it’s clear that the optimised pipeline is more performant (Table 7). Not only does the pipeline remain competitive in recall, it beats (Wang et al. 2024)’s best performances in every other metric by wide margings in all but precision. So, in effect, the pipeline offers a similar precision/recall tradeoff, shown in (Figure 6) and (Figure 7), to instances of (Wang et al. 2024)’s best performing models, all while outperforming each of them in every other metric.

What’s more, it does so across CLEF2018 and CLEF2019 as well. Conclusively marking this work’s model and approach as a clear improvement over (Wang et al. 2024)’s.

max_recall metric. The highest scores for each metric for each dataset is bolded.

| Dataset | Work | Precision | Recall | B-AC | F3 | WSS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLEF2017 | (Wang et al. 2024) | 0.08 | 0.99 | 0.72 | 0.35 | 0.5 |

| This | 0.09 | 0.94 | 0.89 | 0.48 | 0.81 | |

| CLEF2018 | (Wang et al. 2024) | 0.09 | 0.99 | 0.75 | 0.38 | 0.54 |

| This | 0.14 | 0.97 | 0.92 | 0.60 | 0.83 | |

| CLEF2019 | (Wang et al. 2024) | 0.10 | 0.99 | 0.73 | 0.37 | 0.52 |

| This | 0.10 | 0.95 | 0.83 | 0.47 | 0.68 |

future directions

Despite promising results, it’s clear that the potential of multi-stage language model pipeline for automated citations creening has yet to be fully explored. There are still open questions and problems around that need addressing, such as: the impact of LM choice on pipeline performance, the impact of training set on generalisability, the challenge of consistent performance, and more.

With that in mind, some immediate future areas of research are:

-

Prompt optimisers and training parameters:

MIPROv2was used for final optimisation andBootstrapFewShotWithRandomSearchwas only briefly used with development, both of which with default parameters. So, there is room for other automated prompt optimisers and or the selection of better training parameters to provide even greater performance uplift and tackle shortcomings in consistency. -

Training set size and diversity:

The final optimised pipeline variants were trained exclusively on a randomly sampled subset of 24 SRs from the CLEF2019 dataset. There’s a chance training on such a restricted sample overfits the classifier to the domain and topic of the reviews in the training set. Begging the question as to whether larger and more diverse training sets could offer truly generalisable classifiers.

-

Pipeline design and language model choice:

While a few pipeline design iterations were conducted, the final design was heavily inspired by (Delgado-Chaves et al. 2025)’s approach. It also made exclusive use of Chain of Thought as a prompting technique for each of its stages. This suggests that there is still a lot of room to explore the pipeline design space, including the choice of LM to be used for specific stage calls. DSPy makes it easy for different stages to be called by different LMs, enabling future designs to capitalise on the different strengths of different LMs at different stages to maximise overall performance.

-

Full-text screening:

This paper only looked to automate initial, title/abstract screening. It remains to be seen whether this approach more broadly, let alone this pipeline design, generalises to full-text screening.

conclusion

This work set out to take a meaningful step towards the ideal of expert-independent, fully-automated citation screening. It achieved this through the design and implementation of a multi-stage LLM-driven pipeline that performs initial title/abstract screening, using nothing more than a systematic review’s title and a candidate citation’s title and abstract as input. Trained and evaluated on open datasets of biomedical reviews, the pipeline demonstrated promising, state-of-the-art results, significantly outperforming previous works.

With that said, the presented pipeline is not yet a complete solution ready to be used in immediate practice. Challenges with inconsistent performance and generalisability have yet to be solved, limiting its reliability. This calls for more work to be done on designing, optimising, and evaluating this approach of using language model pipelines to fully-automate citation screening.

references

-

In practice, citation screening is typically conducted in 2 stages: title & abstract screening and full-text screening (Ofori-Boateng et al. 2024). Existing works exploring the automation of screening have usually targetted on or the other, formalising their classification tasks differently and relying on different citation features in the process. ↩︎

-

The penultimate datapoint was not included in the SYNERGY dataset since it only included full-text inclusion data to begin with. This didn’t pose a problem because of how quickly it was replaced by CLEF2019. ↩︎

-

Note that Work Saved from Sampling \(WSS = \frac{TN+FN}{N} - (1-r)\) was calculated with recall level \(r\) set to 1 throughout, to align with (Wang et al. 2024)’s approach. ↩︎

-

Note that more demanding prompting techniques such as DSPy’s

MultiChainComparisonmodule were played around with but not thoroughly tested. So it’s possible for CoT to be outdone by more sophisticated prompting techniques. ↩︎ -

With the exception of the

straight_validateoptimised variatns on Review III. ↩︎ -

Note that (Wang et al. 2024) reports results on the new reviews introduced in CLEF2019 by review topic type (i.e. Diagnostic Test Accuracy and Intervention). So, the highest scores between the 2 were selected for (Table 7). ↩︎