causal theories of reference solve informative identity

introduction

We are concerned with the informative identity puzzle: explaining the substantive quality of non-trivial identity statements with coreferring names. In particular, how true sentences of the form “\(a\) is \(b\)”, for two different names \(a\) and \(b\), can be in any way informative if \(a\) and \(b\) share the same reference. I will argue that causal theories of reference, as Kripke conceived them, can do away with this problem while remaining reductive, by representing the informative content of such identity statements as an expression of a non-trivial identity relation between distinct causal chains that corefer. For it is possible to understand causal chains as different from causal networks, where a causal chain is a specific path through an object’s (referent) causal network, causally linking the use of a name to the object it was originally baptised to. Hence showing that there may exist multiple causal chains in the same causal network, whose relationship is not necessarily made obvious to a speaker using coreferring names.

I will begin with a brief overview of causal-historical theory before elaborating this causal chain versus causal network distinction, touching on how this particular interpretation fits into the wider context of reference theories, before addressing how it resolves the informative identity puzzle and other objections that could be raised against it.

causal-historical theories of references

The core of causal-historical theories, as Kripke envisioned, lies in two primary characteristics:

- That a “naming ceremony” or “baptism” acts as an event that associates a particular name with an object.1

- And that causal links are established from one user of a name to the next and can trace any given utterance of a name to its baptism to a particular object through a causal chain.

These alone form a powerful foundation for a compelling theory of reference in which names refer not by way of association with some descriptive content, but through a causal chain linking a name’s utterance to the original event that brought it into association with a particular object, its referent.

One of the key advantages of this approach is its simplicity. Compared to Russelian descriptions, for example, where the definite and indefinite uses of names take on translated “logical forms” to establish their sentence meaning, causal theories provide a much more intuitive account of the relationship between names and referents that is easier to reason about. And they do so without suffering the kind of damning objections theories like Russel’s face: like the handling of empty terms and the law of the excluded middle.

With that said, causal-theories require some embellishments to account for more prickly aspects of language, namely name ambiguity, which occurs when a name has multiple referents. For example, the first name “Alex” has been shared by many over the years, creating ambiguity surrounding who exactly we are referring to when employing it. And although causal theory treats each bearer of the name “Alex” as having distinct historical-causal groundings, due to their independent baptisms, this is where some would consider speaker intentionality to be a third crucial component to a more complete or robust causal theory of reference, at the expense of becoming a less reductive one. A seemingly fair objection that will be addressed further on.

causal chains vs causal networks: informative identity

Kripke’s outline for a causal theory of reference lacks refinement to stand up to serious scrutiny. The hope is to try and preserve the theory’s simplicity without making any changes to its fundamental tenets previously listed, and without introducing any unecessary conceptual baggage that could weigh it down. With that in mind, I think it’s important to draw a distinction between the idea of a causal network and a causal chain, a distinction I will show empowers causal theory with an interpretation capable of resolving informative identity alongside other objections.

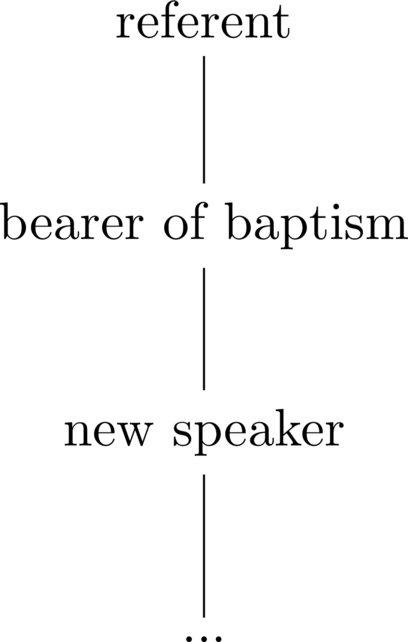

A causal chain is defined as a series of links from the naming ceremony of a referent to a particular speaker. In a more formal sense, the concept has a recursive definition whereby the causal chain of any individual is given by the causal chain of the person who introduced the name to them, conjoined with the new link between that person and our individual. And where the performer of the naming ceremony has a causal chain of a single link. With this, we can visualize the baptism of an object and the propagation of its name as a tree like structure with the referent as the root and the bearer of the baptism as the first child node, as seen below.

The passing on of the name to subsequent speakers is then represented by the successive addition of child nodes to the leaf node of the tree, where a leaf node (borrowed from graph theory), is simply a node with no children. In this way, there is a unique path from the root of the tree to the leaf node that passes through all intermediary nodes. Interpreting this path as a causal chain, we can understand each speaker’s chain as a subset of this one.

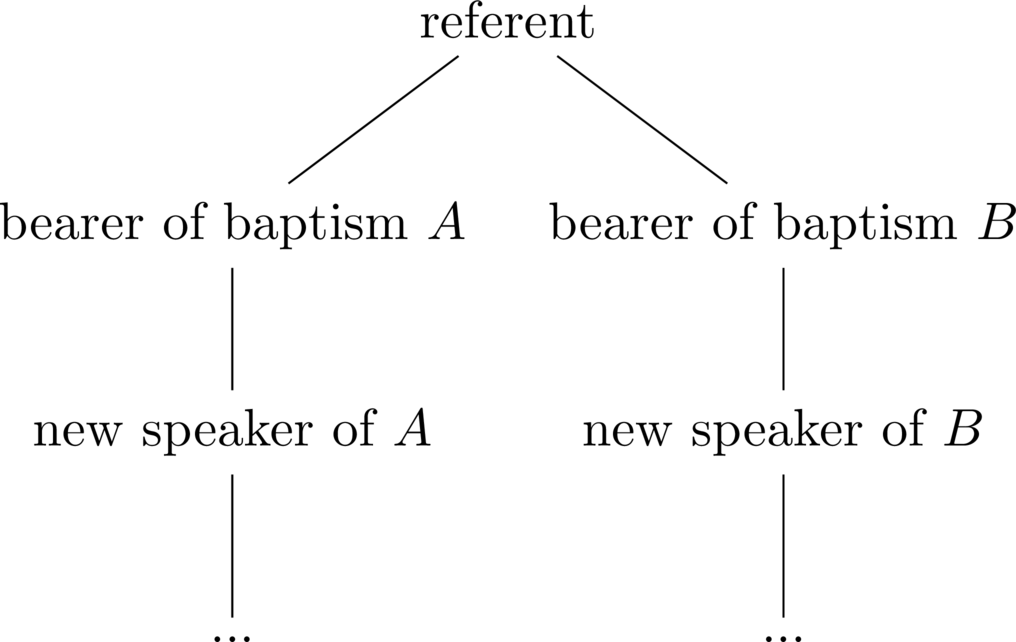

However, the informative identity puzzle asks us to consider when a referent has multiple names, which we can represent as a root with more than one child node:

We call such a tree whose root has more than one node a causal network; because it is comprised of multiple distinct causal chains (paths to a leaf node). Similarly, we speak of a name’s causal chain but a referent’s causal network, from which it becomes apparent that a given speaker can exist across multiple causal chains of a particular referent’s causal network.

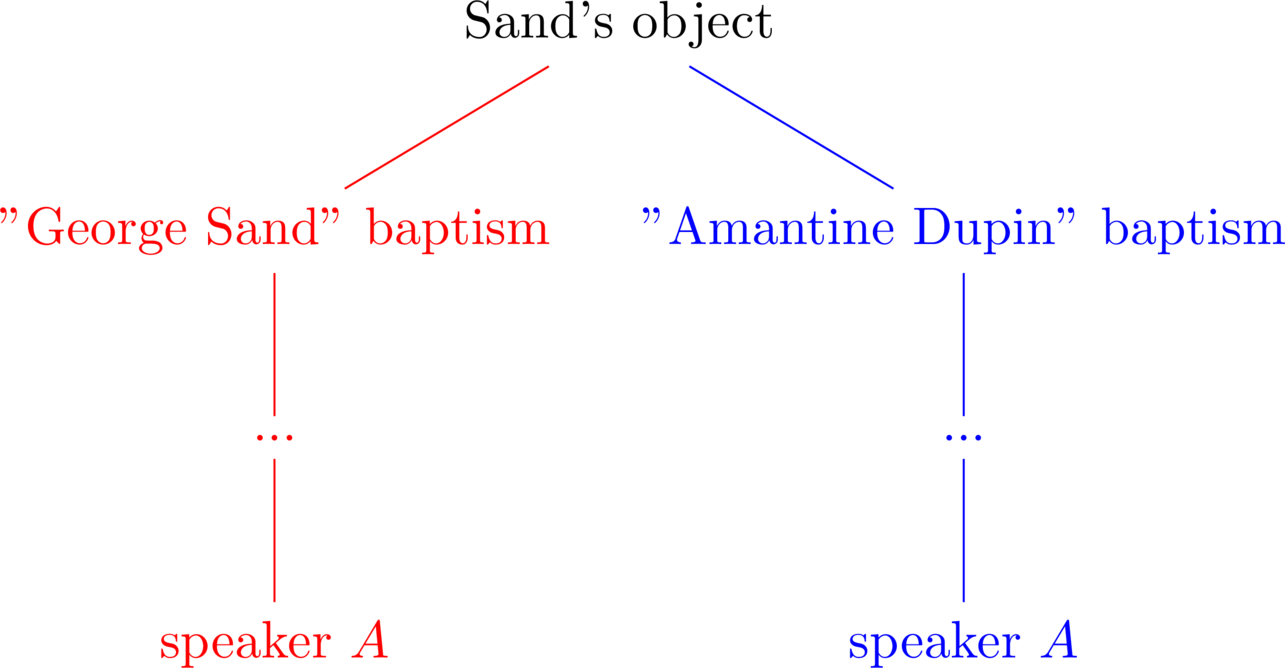

Let us then model an example of an informative identity problem; that is, a sentence in which two distinct names, referring to the same root object, can still be informative (non-trivial). Consider the sentence “George Sand is Amantine Dupin” for some speaker \(A\), linking the 19th century french author to her pen name.:

The trivial statement “George Sand is George Sand”, remains trivial as it only affirms that a causal chain is itself. More precisely, it affirms that the object ensured by the causal chain “George Sand” (red) is the object ensured by the causal chain “George Sand” (red). The non-trivial case on the other hand, affirms that the object ensured by the causal chain “George Sand” (red) is also the object ensured by the causal chain “Amantine Dupin” (blue). And given that these are two distinct causal chains, we are claiming an identity between different causal chains in their resolution in a common root. In other words, we are informing a listener that two distinct causal chains are in fact part of the same causal network, a non-trivial fact.

This is because, in initiating a speaker to a causal chain, one is not making them explicitly aware of all the preceding links that tie them back to the root, only guaranteeing that such a series of links does in fact exist. In doing so, a newly initiated speaker is not made aware of the intermediary nodes along its causal chain, let alone the extent of the causal network their chain is a part of.

Ultimately, entering causal chains is always done at the extremities of a causal network. This hides the full details and complexities of a network to its newly inducted speakers, in turn, allowing for informative identity claims to be made to its members.

objections

reference ambiguity: a non-reductive theory

In spite of the elegance with which causal-historical theories can account for reference puzzles like informative identity, some would argue that these theories are incomplete or unsatisfactory, undermining the value of their contribution to discussions on reference. In particular, the difficulties causal theories face in explaining the use and resolution of naming ambiguities without the introduction of more complex theoretical elements like speaker intention. Especially when such additions only tarnish causal theories’ simplicity, opening them to criticism of being non-reductive. And while I concede that added complexity detracts from the appeal of causal theories, I would argue that the expectation for these theories to account for naming ambiguities in the first place, is plainly unfair.

Theories of reference, like all theories, are postulated explanations of selected phenomena, in this case: the observed feature of names referring (to objects) in language. As a result, a successful theory of reference is one that provides a convincing description of the relationship between linguistic devices, like names, and the world. Given that naming ambiguity is an observed feature of language, a successful theory must also, by extension, account for how naming ambiguities can arise. Namely, how names can have multiple referents. But, importantly, a successful theory must not necessarily explain how speakers/users of language resolve their naming ambiguities. As this is a completely separate theoretical challenge to that of reference: one explores the link between linguistic devices and the world, the other how the ambiguity of linguistic devices can be resolved by its users.

And this distinction is important.

It’s not to say there can be no generalised/universal or combined theory that accounts for both reference and ambiguity. I am simply claiming that to critise a theory of reference on the basis of its inability to explain ambiguity, a separate albeit related problem, is simply not fair criticism. Particularly when all theories can be criticized for not exceeding the limits of their own scope.

For the purposes of this discussion then, ideas like speaker intentionality, including more sophisticated contributions like Grice’s work, should be considered as separate theories entirely, focused on another feature of language: disambiguation.

And even then, disambiguation is an almost separate, more general problem of which multi-referent names in natural language is just an instantiation2. After all, disambiguation, in the abstract, is just a decision procedure that details how to make a selection from a collection of alternatives. These alternatives just happen to be referents in the context of language and reference theory, compared to strings of 0s and 1s in signal processing and data transmission, for example.

What’s more, disambiguation in language lies in the realm of speaker meaning, where it’s perfectly conceivable for users of a same language to disambiguate their messages in a number of different ways, including ways that are potentially inconsistent between certain groups of speakers3. An observation that strongly suggests that disambiguation lies with the interpreter and not the language. A point best exemplified by the recent large language artificial intelligence models and their undeniable mastery of written communication. Seeing as it is not only conceivable but rather likely, that the mechanisms by which such computational models resolve ambiguities differs to those of human users of language. Further highlighting the difference in concerns facing a theory of reference and one of ambiguity.

conclusion

Causal-historical theories of reference can elegantly solve the informative identity puzzle with a unique simplicity that undermines competing accounts like descriptivism. The uncontroversial interpretation of causal-networks and causal-chains provide a clear account of not only how coreferring names can be brought about, but also how the independent baptism and evolution of these names, can explain the informative content of identity claims between them. And although original causal theories may disappoint in their inability to account for naming ambiguities, it in no way detracts from the compelling solution they present to the explicit problem they look to solve: reference.

-

Importantly, the object in question needn’t be one of the “physical world”. Abstract and fictional objects can be incorporated into a causal theory by way of a “baptism by description”. A feature that makes intuitive sense if you consider disciplines like mathematics and logic where abstract objects are initiated by definition. Nonetheless, such a feature will not be directly considered here. The default baptism by ostension will be assumed. ↩︎

-

Interestingly, formal languages like programming languages share the same problem: variables can be mistakenly defined with the same variable names. When the program is then ran, errors are thrown raising a naming ambiguity issue. But unlike language, it just so happens that the deterministic nature of computing has 0 tolerance for ambiguity. ↩︎

-

Unless there is compelling evidence to believe that people happen to disambiguate linguistic devices like names, in the exact same way to begin with. ↩︎